(DIYA TV) — With the recent death of Supreme Court Justice Antonin Scalia, much of the political narratives have been pointed towards the actions president Barack Obama will take in appointing a new justice, and the efforts the Republican Senate will undertake to block said action. The third week of February also holds a grim piece of history for the court — on Feb. 19, 1923, the court unanimously ruled to bar South Asians from becoming citizens of the United States and to denaturalize those who had already done so in the landmark decision,United States v. Bhagat Singh Thind.

Thind, who immigrated to the U.S. in 1913 and trained at Camp Lewis to fight for the red, white and blue in World War I, began his attempt to gain American citizenship five years prior to the ruling in 1918. The high court’s decision effectively squashed whatever hopes Thind, and his fellow South Asians, had in becoming naturalized citizens. It was not until a full two decades later, in 1946, that South Asians would be again allowed the right of citizenship.

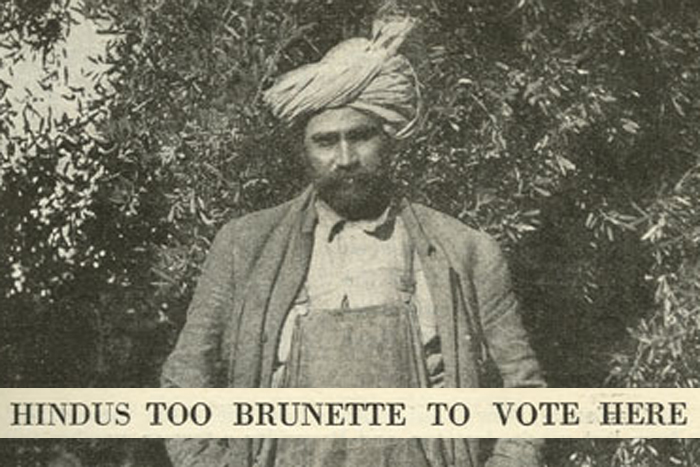

A Literary Digest article, published in 1923 and titled “Hindus Too Brunette to Vote Here,” providing an explanation of the times, and the racial logic which was used by the court to render its verdict. Thind, arguing what he referred to as “racial science,” claimed that he and his fellow South Asians were as “white” as the rest of Americans walking around the country. South Asians were descendants of Indian Aryans who belonged to the “Caucasian race,” he said before the court. Based on this, Thind said since he and other South Asians were indeed “white,” they should be eligible for citizenship.

The Supreme Court responded:

“It would be obviously illogical to convert words of common speech used in a statute into words of scientific terminology when neither the latter nor science, for whose purpose they were coined, was within the contemplation of the framers of the statute are to be interpreted in accordance with the understanding of the common man, from whose vocabulary they were taken.